Column

Two Lockheed Martin C-130 Hercules planes of the Bangladesh Air Force. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The strategic challenge faced by Bangladesh on its doorstep is the increasing influence of India and China in Myanmar's Rakhine State, where the two great powers of Asia are engaged in building deep water ports. India's planned Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Project aims to bypass Bangladesh in linking Northeast India with the port of Kolkata through Myanmar and the Bay of Bengal. India is developing the Sittwe Port in Rakhine State as a gateway to its landlocked northeastern states. China is developing the Kyaukphyu Deep-Sea Port as part of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) which aims to bypass the Malacca Straits for Chinese shipping and oil and gas pipelines.

The civil war in Myanmar has resulted in the country's junta losing control of much of the nation's territory, including most of Rakhine State. The Arakan Army now effectively controls Rakhine State, including the townships along the Bangladesh-Myanmar border. 90% of the Arakan Army's financial resources originate in China. Most of the Arakan Army's weaponry also originates from China and is supplied by a clandestine network of ethnic insurgents stretching from Shan State on the border with Yunnan to the shores of Rakhine State. Chinese intelligence agencies have cultivated robust links with Myanmar's myriad rebel groups, including the Arakan Army.

The Arakan Army has obstructed India's Kaladan Multimodal Project. But the Arakan Army has not attacked Chinese projects. India's Kaladan project has been paralyzed by the Arakan Army's takeover of Rakhine State. Does the paralysis and obstruction of the controversial Kaladan project benefit the national interest of Bangladesh? The Kaladan project was undertaken amid silence by India's BJP government on the Rohingya genocide. India has not condemned Myanmar's junta for the Rohingya genocide and has made lackluster efforts to support Rohingya repatriation.

There have been growing calls for an international humanitarian corridor under the auspices of the United Nations to deliver aid to the people of Rakhine State. There is an increasing risk of famine in Rakhine State. Jordan and the UAE recently air dropped humanitarian aid in the Gaza Strip after Israel undertook a tactical pause in its military offensive. The possibility of air dropping aid for the beleaguered population in Rakhine State can also be seriously considered amid reports of a famine in Myanmar. Bangladesh has the capacity to air drop both military and humanitarian aid in Rakhine State. The Bangladesh Air Force operates a fleet of five C-130J Super Hercules and three C-130 Hercules aircraft built by Lockheed Martin. State-of-the-art drones from the Turkish aerospace firm Baykar can support reconnaissance and light combat operations.

In recent years, the Bangladesh Air Force has deployed its C-130 fleet for regional humanitarian operations, including air lifting Maldivian students from Bangladesh during the Covid-19 pandemic and delivering aid to Nepal after an earthquake. Most recently, the BAF has deployed its C-130 fleet to deliver aid to Myanmar after a devastating earthquake struck the Mandalay region. The Bangladesh Navy has also deployed its frigates to support humanitarian aid deliveries, including aid for earthquake victims in Myanmar and water desalinization equipment for the Maldives where a water shortage threatened the capital city of Male.

In the past, American B17 bombers airlifted Tibetan guerillas from Dhaka Airport during the 1950s. In 1971, the Indian Air Force air lifted and air dropped Bengali guerillas during the Liberation War which transformed East Pakistan into Bangladesh. A little-known fact of airdrops in South Asia is that the Nizam of Hyderabad arranged an air drop of weapons from an Australian arms dealer before the Indian annexation of Hyderabad State in 1948. Hypothetically, Bangladesh can deploy its logistical fleet to supply arms and aid to rebels in Myanmar, including through air drops by C-130 planes, clandestine supplies from navy ships, and back up aid deliveries with unmanned aerial surveillance, reconnaissance and combat.

Bangladesh has to increase its strategic depth in the region. Enabling a humanitarian channel, backing credible groups which seek a solution to the Rohingya question, and delivering life-saving aid for Myanmar's beleaguered people can increase the strategic depth of Bangladesh. The Arakan Army, which now controls Rakhine State, has imposed harsh conditions for the Rohingya population. According to Human Rights Watch, life for Rohingya people under the Arakan Army is "incredibly restrictive".

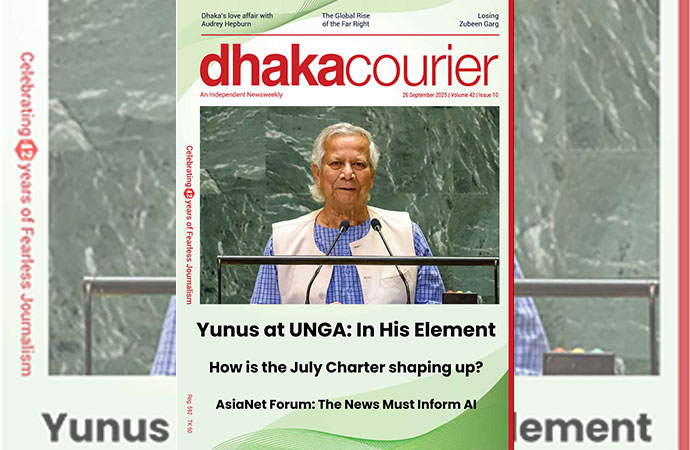

While the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus and his National Security Adviser Khalilur Rahman has been open to the idea of a UN-backed humanitarian channel; doubts remain on whether such a humanitarian initiative can lead to immediate Rohingya repatriation. The Arakan Army is not a viable option for Bangladesh to support if it continues to persecute the Rohingya people in Myanmar.

Some have considered Bangladesh as a "buffer state" between India and China. Should Bangladesh be a buffer state for India and China to ward off Western influence in the region? Or should Bangladesh become a strategic player on its own terms by balancing competing interests and defending its national interest?

Bangladesh has a deep strategic partnership with China which forms the crucible of its strategic autonomy. The military will be extremely mindful of Chinese concerns. It will also take into account Indian concerns of potential Western support for radical elements similar to the US support for the Afghan mujahadeen in Pakistan during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The last thing Bangladesh would want is for any humanitarian corridor to be exploited by radical groups to ferment extremism.

Opening a humanitarian corridor can allow Bangladesh to gain influence and leverage in the strategic competition with India's far-right that has cultivated strong ties with Myanmar's hardline Buddhist nationalist junta. It would also undermine Indian efforts to bypass Bangladesh in developing trade routes in the region.

Bangladesh's capacity to strategically compete with India and China can be traced back to East Pakistan's role in serving as a springboard and launchpad for secret proxy wars in Tibet, Northeast India and Burma. In 1950, sections of the Rohingya population in Arakan revolted against the Burmese state. Burma's first Prime Minister U Nu reached out to Pakistan to reign in the rebels who received sympathy and support from across the border in Chittagong. The Burmese permitted the opening of a Pakistani consulate in Sittwe to deal with the troubles.

Speaking in 1957 during a joint session of the Philippines Congress, the East Pakistani statesman Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy remarked that "As long as grievous wrongs remained unredressed and as long as the right of self-determination was denied to peoples and UN decisions were flouted or evaded, lasting peace would remain a mirage." It was around this time that American B17 bombers began airlifting Tibetan guerrillas from what is now Dhaka International Airport. The first B17 bomber took off from Dhaka's Kurmitola airfield in October 1957. The air strip was built by the British during World War II and used by the Allied forces to support China against Japan and operations in Burma. In November 1957, the second B17 flight took off from Dhaka. The CIA initiated the B17 flights from Dhaka as part of its secret war in Tibet. The B17 flights flew over Indian territory and airdropped American-trained guerrillas in Tibet. East Pakistan was a key part of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the government of Pakistan gave permission for airlifting Tibetan guerrillas.

In the winter of 1963-64, the Mizo National Front in northeastern India established contacts with the government of East Pakistan. Led by an accountant named Laldenga, the Mizo rebel group sought arms and aid to fight the Indian state in Mizoram, which bordered the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In 1971, the Indian armed forces airlifted Bangladeshi freedom fighters to and from training camps in the northeast. By 1975, strategic rivalry erupted between Indian and Bangladeshi intelligence agencies. Between 1975 and 1997, India supported insurgents in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Bangladesh provided clandestine support to rebels in Assam, including the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA). By 2009, the government of Bangladesh adopted a zero-tolerance policy against Indian insurgent networks. Dhaka could theoretically revive its capacity for supporting proxy insurgents in Myanmar on the premise of aiding the people of Myanmar in their struggle for democracy and to achieve the self-determination and right of return of Rohingya refugees in their Arakanese homeland.

Umran Chowdhury is Assistant Editor of the Dhaka Courier and a Research Associate at the Cosmos Foundation and Bay of Bengal Institute.

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Religion and Politics: A Toxic ...

At Dhaka University, cafeteria workers have been told not to wear shor ...

Enayetullah Khan joins AsiaNet ...

AsiaNet’s annual board meeting and forum was held in Singapore, ...

In a New York minute

Many leaders back a UN call to address challenges to ..

Defaulted loans at Non-Bank Financial Institutions ( ..

How the late Zubeen Garg embodied cultural affinitie ..